The current struggle for religious freedom on the national level calls to mind a similar struggle in Arkansas that began 99 years ago and lasted for several years.

In February 1913, a bill was introduced into the Arkansas State Senate whereby convents and monasteries dedicated to the education of youth would be under state surveillance, which in practice meant that the local sheriff or his deputies would be able to inspect the facilities any time as many as 20 voters demanded it. Soon after that, another bill extended the surveillance and inspection to religious hospitals and parish schools. The bill had passed 50 to 18 in the House of Representatives on March 1, 1913, but did not have the votes in the Senate to bring it to Gov. Joseph Taylor Robinson's desk.

But two years later Rep. Robert R. Posey of Grant County reintroduced the bill and got it through both houses of the General Assembly; it was signed by Gov. George Washington Hays in March 1915. Our diocesan paper, The Southern Guardian, had vigorously opposed the bill and asked the governor to veto it, but he signed it. There was heated opposition to the Posey Act in non-Catholic circles as well, especially by State Sens. George Jones of Pulaski County and Lewis Josephs of Miller County, who called it a violation of federal and state constitutions and a clear violation of religious freedom. The law, though not widely enforced, remained on the books until it was repealed in 1937.

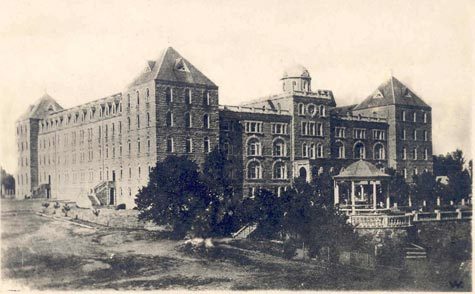

The law apparently gave teeth to two searches of Subiaco Abbey in 1918. Several of the monks had come from Switzerland and were originally German-speaking, which aroused suspicion of their patriotism during World War I. The governor received letters denouncing the monastery and demanding a search for the munitions allegedly warehoused in the "great cellar." He in turn mandated the local sheriff to conduct the search in January 1918. The sheriff was a friend of the abbey and very embarrassed by the assignment. He meant to come to the front door, introduce himself and then leave as quickly as possible. But Father Justin Wewer required him to conduct a thorough search so that he could speak with authority when he reported that nothing suspicious had been found in the abbey.

In April another search was conducted, this time by the National Postal Service, which had been assigned this investigatory work by the government. In response to complaints against Subiaco Abbey received in Washington, the postal department sent orders for an investigation to the Memphis department, which in turn assigned the investigation to the postmaster in Fort Smith. One of the complaints maintained that the abbey buildings were 13 stories high, with seven floors underground filled with munitions.

Like the sheriff earlier, the postmaster was very embarrassed by the assignment, but he was received cordially and conducted through every area of the monastery. He submitted a report stating that he had found no munitions nor any other suspicious supplies. Throughout the war the monks tried unsuccessfully to clarify that they had come years ago from Switzerland, a neutral country, not Germany.

Abbot Jerome Kodell, OSB, has led Subiaco Abbey since 1989.

Please read our Comments Policy before posting.

Article comments powered by Disqus St. Paul says: How does the Bible define love?

St. Paul says: How does the Bible define love?

6 steps to getting married in Diocese of Little Rock

6 steps to getting married in Diocese of Little Rock

Most frequently asked questions on Catholic marriage

Most frequently asked questions on Catholic marriage

St. Timothy winner recommends adoration to other teens

St. Timothy winner recommends adoration to other teens

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist