PIGGOTT — At the top of a hill on the outskirts of Piggott stands the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center, a two-story home surrounded by dogwood trees and daffodils in the spring. Nestled behind the house is a barn-studio filled with memorabilia from an important era of American literature.

Purchased in 1997 by Arkansas State University in Jonesboro, the museum’s purpose is to “contribute to the regional, national and global understanding of the 1920s and 1930s eras by focusing on the internationally connected Pfeiffer family of Piggott and their son-in-law, Ernest Hemingway.”

Dr. Ruth A. Hawkins, project director of the museum’s restoration team and author of “Unbelievable Happiness and Final Sorrow” — the story of Hemingway and Pauline Pfeiffer’s 13-year marriage — writes in detail about the Pfeiffer family’s contribution to Hemingway’s literary career.

In her book preface, she wrote, “When I began researching Pauline Pfeiffer Hemingway nearly 15 years ago, I was surprised at what little attention the Pfeiffers had received.”

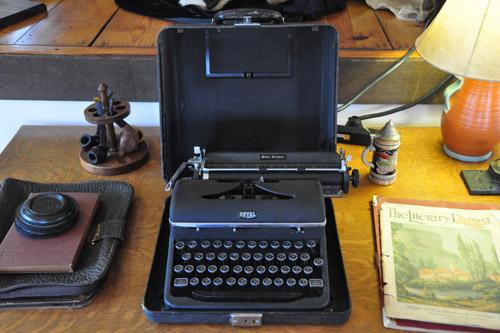

In the book, Pauline is described as “her husband’s best editor and critic and her wealthy family provided moral and financial support, including the conversion of an old barn to a dedicated writing studio at the family home in Piggott, Arkansas.”

According to the museum’s timeline, Hemingway completed the first draft of “Farewell to Arms” in the barn-studio while awaiting the birth of their first child in 1928. Today in the barn-studio, visitors find an impressive mural of original photographs retracing the couple’s safari trip in 1933 that include quotes from Pauline Pfeiffer’s diary of the trip, along with several animal trophies. Hemingway’s work, “Green Hills of Africa” is based on the safari. It is thought that Hemingway used his Piggott visits as a way to remain in seclusion from fellow writers and publishers.

While visiting the museum the family’s Catholic faith and commitment to social justice might be overlooked.

Although Pauline Pfeiffer-Hemingway’s father, Paul, had accumulated his wealth through the family’s business, Pfeiffer Pharmaceuticals along with his brothers Henry and Gustavus in St. Louis, his primary interest was in acquiring farmland. In 1902 when he discovered the rich bottom land of the St. Francis River near Piggott, he began buying various tracts there that came to include some 60,000 acres.

Then in 1913 Paul Pfeiffer moved his family — wife Mary and their children Pauline, Karl, Virginia and Paul Max — to Piggott after promising Mary, an Irish Catholic, her own private chapel.

“Mary’s parents had both immigrated from Ireland at the height of the religious persecution there during the potato famine,” Hawkins said. “Daniel Downey, her father, vowed that when he arrived in the United States and had his own family he would have a chapel in his home where his family could worship whenever and however they wished.”

Shortly after their arrival in Piggott, Paul Pfeiffer (though not Catholic himself) fulfilled this promise by creating a private chapel in the home where Mary said her prayers daily.

Museum tour guide Karen Trout said, “The priest would come to Piggott at least once a month to say Mass for Mary and her children. Otherwise, she and her children would ride the train to Paragould 30 miles to attend services at St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Sundays.”

The couple’s youngest son, Max, died during an influenza outbreak in 1918. It was also in 1918 that Pauline, their oldest daughter, graduated from the University of Missouri School of Journalism and began her writing career. This eventually would lead her to Paris to work for Vogue magazine and the opportunity to meet Ernest Hemingway, along with other writers and artists of that era.

“When Ernest divorced his first wife to marry Pauline Pfeiffer (in 1927), Mary was devastated that her daughter was part of breaking up a marriage and she had a difficult time coming to terms with it and prayed deeply about it,” Hawkins said. “While her son-in-law Ernest professed to be Catholic, I’m not so sure he was. However, I do know that Ernest was in awe of Mary and influenced by Mary’s strong beliefs and the way she accepted him as a son, even though it was not easy to do.”

Hawkins found more information about Mary’s faith in one of her letters dated May 10, 1927, which is kept at the Princeton University Library.

“Mary wrote the couple a letter on their wedding day in which she said, in part, ‘For many months I have been asking our Heavenly Father to make the crooked ways straight and your life’s pathway one of peace and happiness, and this morning. I feel a quiet assurance that my prayers have not been in vain … Commending you to the care of One who always knows what is best for his children, I am not without tears, but which I promise will be all wiped away before you see me.’”

As a couple, Paul and Mary Pfeiffer were a force to be reckoned with as the reputation of their efforts to help the people of Piggott and surrounding communities grew during the 1930s Great Depression and the New Deal.

Leonard Bradberry, another museum tour guide, said, “I believe in Paul’s and Mary’s dreams and purposeful calling in life, although they were very private people.”

Bradberry said they made efforts to help the community.

“Throughout the Depression, the homeless and hobos were fed on the house’s summer porch, interviewed to understand their personal needs and then sent to the stores on the ‘court square’ to acquire the things they were in need of. Paul would then pay each store what they were owed. Paul especially looked forward to giving gifts at Christmastime,” she said.

“Mrs. Pfeiffer gave instructions for food to be made available 24 hours a day by keeping meals warm on the kitchen stove. She also insisted that those in need be fed with her good dishes and silverware. She wanted, regardless of their circumstances, to ensure her guests’ dignity,” Bradberry said.

Trout agreed.

“Mr. Pfeiffer was extremely helpful in his dealings with the farmers working on his land,” Trout said. “When it was time to settle up after a harvest and it had been a difficult year, Mr. Pfeiffer just worked it out so the farmers could make it up the next year. He believed in a ‘hand up’, not a ‘hand out.’”

In the Pfeiffer museum, there is a quilt closet that was used to store quilts that the women of Piggott would make and sell during those difficult years.

“The quilt pieces were made from the clothes of farm families worn on a daily basis. Their sweat, energy and life were in those scraps of clothing,” Bradberry said. “Once it could no longer be worn, the clothing was used in the making of quilts. When area women offered these quilts for sale at the Pfeiffer home, the housekeeper was instructed to purchase any quilt regardless of its quality or condition at the current retail price in the catalogs. They were then stored in the ‘quilt room’ and in turn to be gifted to anyone — the hobos, homeless, etc. — who might come to the home, needing a good quilt.”

After the breakup of the Hemingway-Pfeiffer marriage in 1940, Pauline, with her two sons and her sister Virginia, settled in California. Her father Paul died in 1944, followed by her mother Mary’s death in 1950. Pauline died in 1951.

The Pfeiffer home and property were sold to Tom and Beatrice Janes in 1950. On June 24, 1982, the Pfeiffer home was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In April 1997, ASU bought the Pfeiffer family home from Beatrice Janes and acquired the barn-studio from her son, Bruce Janes. The grand opening of the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center took place July 4-5, 1999.

Of the children in the Pfeiffer family, son Karl and his wife Matilda remained in Piggott, near his parents on adjoining property until his death in 1981. His home, originally built in 1933, now houses the Matilda and Karl Pfeiffer Museum and Study Center. On display are the Native American Artifacts Collection and the Matilda Pfeiffer Mineral Collection.

Please read our Comments Policy before posting.

Article comments powered by Disqus 'Cabrini' film tells story of saint with great faith

'Cabrini' film tells story of saint with great faith

Bishop Taylor announces more pastoral appointments

Bishop Taylor announces more pastoral appointments

Most U.S. Catholics approve of Pope Francis, Pew says

Most U.S. Catholics approve of Pope Francis, Pew says

Winning directory photo honors Our Lady of Guadalupe

Winning directory photo honors Our Lady of Guadalupe

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist