Walking up to the altar at the Cathedral of St. Andrew, little altar boy Joe Biltz was responsible for carrying the cappa magna, or “great cape” for the bishop. Sometimes six pews ahead, the eighth-grader walked slowly and steadily, keeping the straight and narrow path. It was a portrait of traditional 1940s Catholicism.

“He went from being a little altar boy with the shiny shoes and combed hair into a revolutionary,” Msgr. John O’Donnell said.

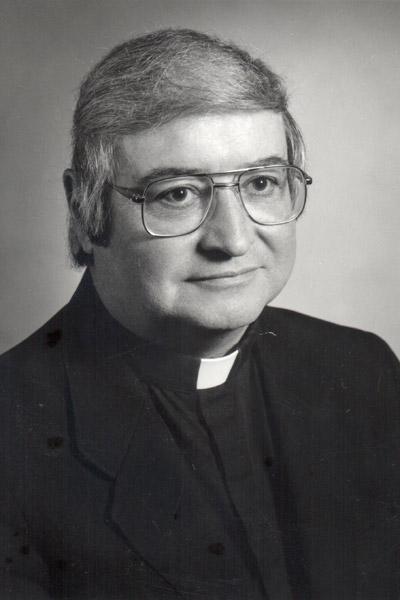

Father Joseph Henri Biltz, a diocesan priest in Little Rock from 1955 until his death in 1987, quickly learned to walk outside the aisle, living the life of a prophet. He had the fire of the Holy Spirit burning in his soul, crying out the Beatitudes through his work for society’s oppressed. Even 30 years after his death, his fight for social justice rings true.

“Although I never met Father Joseph Biltz, I was introduced to his story shortly after arriving in Little Rock when I used the Biltz Room at the St. John Center for the first time. It is clear that his witness to social justice touched many hearts and continues to inspire even today, 30 years after his death,” said Bishop Anthony B. Taylor. “Yet sadly, we still struggle today with the same issues on which he sought so courageously to shed the light of the Gospel throughout his priesthood, including among other things racial justice, the human rights of immigrants, nuclear disarmament and the immorality of the death penalty. I thank God for his priesthood and I pray that the Lord will raise up from among us many more faithful witnesses to truth, justice and charity in our world today.”

Father Biltz was ordained for the Diocese of Little Rock at the Cathedral of St. Andrew in May 1955, the first member of Our Lady of the Holy Souls Church in Little Rock ordained a priest, according to a 1955 article in The Guardian (now known as Arkansas Catholic). He was a high-achieving student, earning multiple master’s degrees and a doctorate in moral theology. Attending Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., “formed his passion for justice because he grew up obviously in a very segregated society” and family, said Msgr. O’Donnell, a retired diocesan priest who was ordained in 1954.

Msgr. Scott Friend, vicar general and diocesan vocations director, went to work as a seminarian with Father Biltz during a summer in the 1980s to help organize migrant farm workers in Warren.

“It was an important one for me because that’s where I really saw the need to learn Spanish, and it highly motivated me to do that,” Msgr. Friend said.

Father Biltz organized boycotts through his work with the United Farm Workers in Oregon and Arkansas.

During the trial in Warren of tomato growers who threatened a Catholic migrant minister in 1982, Father Biltz said, “Christians can be like Veronica, wipe his face and comfort him by assisting farm workers to a more human, fuller life.”

As a young seminarian, Msgr. Friend watched in awe the way Father Biltz treated people.

“He was working beyond just the walls of the parishes,” he said. “He embodied the things back then that Pope Francis talks about today.”

Refusing to take a salary, Father Biltz’s example was unlike anything Msgr. Friend had seen, which helped form his understanding of a priest.

“I was so proud of being a Catholic because of the way that he lived out his priesthood,” Msgr. Friend said. “… I think underlying all of this is a great love for the Lord, the Church and people. He brought all those things together.”

In 1978, Father Biltz was named the diocesan director for the Office of Justice and Peace and served in the position for the next nine years. He also served as chairman of the Urban League of Arkansas, a diocesan coordinator for prison ministry, member of what is now known as Just Communities of Arkansas and several other advocacy groups.

Father Warren Harvey, the only African American priest in the Diocese of Little Rock, watched Father Biltz as a young black parishioner in the late 1970s in his desire to advance civil rights.

He discerned his desire to stay in the diocese for his own priesthood, in part because of Father Biltz’s example, he said.

Msgr. O’Donnell met Father Biltz while the two were in seminary and said their friendship was one of support.

“We were looked upon as mavericks, revolutionaries or whatever you want to call us,” and built up a friendship of about five or six social justice-minded priests. “We’d go out to have a drink or dinner some time to laugh about it all. But then other times it was a little tough marching, people heckling you, the cops were behind you,” he said.

“When Joe came along and exposed a lot of things, questioned things like other people had never questioned, myself even, ‘Why do we have segregated schools? Why don’t the black children go to the Catholic school?’”

In 1963, Father Biltz and others organized an institute on racism. While there, he stressed “if the law of the land, the laws of sociology, the laws of economics mean nothing to us, we cannot remain indifferent to the law of Christ. Even if it is difficult to do … only this can extinguish the fires of racial injustice.”

Father Harvey said, “Dr. (Martin Luther) King is my idol in civil rights and Father Biltz is my idol in the Catholic Church.”

On Feb. 8, 1983, Father Biltz testified before the Judiciary Committee of the Arkansas Legislature at the Capitol to support the abolition of the death penalty. It was the year the state adopted lethal injection as an execution method.

“I say today that unless something is done soon, this nation that claims to be under God, will begin to witness a slaughter of precious human life as death row persons are methodically killed,” Father Biltz said.

Freddie Nixon, a member of Pulaski Heights United Methodist Church in Little Rock, met Father Biltz through prison ministry.

“He was befriending and visiting people on death row, and I was doing the same thing,” she said.

Nixon, a board member of the Arkansas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, said Father Biltz was an early supporter of the coalition. He was ecumenical, speaking sometimes at Protestant churches, as many traditional Catholics at the time thought, “We were all going to hell, except them, the conservatives,” Msgr. O’Donnell said.

Father Biltz’s nephew, Father Bill Elser, pastor of Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in Hot Springs Village, said his uncle would still be at the forefront to abolish the death penalty today.

“If he was still here, he’d be railing to our governor and everybody about not putting these people to death; killing is wrong whether it’s in the womb or the person on death row,” Father Elser said. “It’s inspired me to speak about such things at the pulpit.”

In 1995, Nixon was given the Father Joseph H. Biltz Award, by what is now Just Communities of Arkansas, “Which was so meaningful because I loved him,” she said of Father Biltz, who taught her “to never give up working for social justice even when it may look like you’re not going to succeed. Stay committed to what you believe in.”

Just as Jesus flipped the tables of the money changers in the temple and chastised the hypocritical Pharisees, so too did Father Biltz take action while speaking out. In 1983, Father Biltz read the Bible at a Titan II Missile silo in Arkansas while anti-nuclear weapons protester and Catholic convert James Sauder climbed the barbed wire fence to pray, carrying a wooden crucifix in protest.

“The first time he went over the fence at the silo, I saw his action speaking of sanity and morality in a country and world I feel has gone insane with militarism and nuclear immorality,” Father Biltz said in a 1983 Guardian article.

In 1985, more than 40 protestors, including Father Biltz, were arrested in Washington D.C., protesting apartheid policies of South Africa in front of that country’s embassy. More than 1,500 fellow Urban League members peacefully marched, held hands and sang songs, going closer than 500 feet in front of the embassy, which violated the law.

“It’s time for the U.S. government to change its policies and break the back of apartheid,” Father Biltz said in an Aug. 2, 1985, Guardian article.

They were released three hours later.

Bishop Andrew J. McDonald, who served as bishop from 1972 to 2000, wrote in a column about the arrest published in the Aug. 2, 1985 Guardian, saying in part, “Thank God for Father Biltz. Someone from our Church should be there … Father Biltz is like the prophets of old, crying out against injustices.”

The arrest and invitation from Bishop McDonald for readers to respond prompted a page of letters to the editor in the Aug. 30, 1985, edition.

The letters of both support and criticism — one asking “How much longer are we going to have to apologize for Father Biltz’s actions?” — conveyed the pushback he received from some parishioners and Church leaders.

While today it’s common to see priests speaking out on moral issues, Father Biltz broke the mold in Little Rock.

“Roman Catholics were incensed at that — they thought we were a disgrace to the Church, not minding our own business,” Msgr. O’Donnell said. “Why weren’t we in the church praying instead of out in the streets demonstrating?”

His mother, Hilda Biltz, was a secretary for Bishop Albert Fletcher, who served from 1940 to 1972, something Msgr. O’Donnell called “ironic” because of the frequent criticism and at one point suspension Father Biltz received from the bishop.

“He’d mimic Bishop Fletcher. He’d get up, give a little speech the same way Bishop Fletcher would,” Msgr. O’Donnell said. “… Joe had a great sense of humor. At the same time he’d give speeches and demonstrate and kind of rail against everybody — the bishop, the president, everybody. He was fiery.”

Though Father Biltz was driven by his work, his time with family and friends was a chance to relax.

“I found him to be very gentle and quiet, more to himself, reflective,” said Father Elser, who affectionately referred to him as Father Joe rather than “uncle.”

Occasionally, debate would bubble up at a family meal or holiday gathering, as not everyone agreed with his stances.

“I remember the early years my grandmother would step in, ‘OK boys, not here; this is not the place for it,’” and because of Father Biltz’s deep respect for his mother Hilda, that would be the final word, Father Elser said.

“He used to take her to the beauty parlor every week, he’d always kid around that he couldn’t miss that,” Father Elser said. She died three months after Father Biltz.

Msgr. O’Donnell, who was also close to Hilda, said “She’d say, ‘Well, take care of my boy Joe, I don’t know where he is or what he’s doing.’ I said, ‘OK, Mrs. Biltz, we’ll take care of him,’” he laughed.

Father Biltz preached at Father Elser’s first Mass and vested him at his ordination.

“His own example of faithfulness to the Lord and doing the Lord’s work in the world,” is what has been most inspiring in his own priestly ministry, Father Elser said. “It’s not just about what we do at Sunday Mass or ministry in the sacraments, it’s what we do to bring Jesus into the world and try to make the world more Christ-like.”

Though the two were at separate parishes, Msgr. O’Donnell said they’d try to go to Razorback games together or listen on the radio.

“Joe was as passionate about that as he was about integration or justice or whatever, the Hogs,” he laughed, adding “He lived a full life.”

On Nov. 29, 1987, Father Joe Biltz died of a heart attack while taking his usual Sunday stroll around the oval at St. John Center in Little Rock where he lived. He was just 57 years old.

“That was a great pain. We were great friends, he was such a nice guy … it was a sad time for everybody,” Msgr. O’Donnell said.

Msgr. O’Donnell’s funeral Mass homily is still remembered today, with the booming opening of Dylan Thomas’ poem “Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

While the faithful mourned, Marcelino Luna panicked. The 24-year-old undocumented immigrant in Warren had an appointment with Father Biltz the week of his death to help him fill out immigration documents.

“I was left without help,” he said. “I really knew very little of him, but yet, I think he helped me even though he was not with us.”

When he drove to an immigration office in Memphis to turn in his paperwork, he was met by the only man at the office.

“His name was Joe. So he reviewed my papers, my forms. He said who helped you to fill this out?” he said. “He said, ‘You know, this is the first package we’ve gotten that is completed.’”

His work permit, resident card and all other immigration requirements were completed in a seven-week span, something that usually takes years. Today he’s known as Deacon Marcelino Luna, an associate director in the diocesan Faith Formation Office.

“It’s an event in my life I always remember, especially when I am in prayer,” he said. “I thank God for the people in my path, I always remember him. That really impacted my spiritual life to know the presence of God even when we feel abandoned.”

Father Biltz’s legacy is not bound by one cause, the variety of prominent titles or all the adjectives in the dictionary. Even the plaque beside the meeting room on the fourth floor of Morris Hall at St. John Center named the “Biltz Memorial Meeting Room,” though an honor, does not tell the whole story of his impact.

It’s in the vocations director who has changed countless lives: “He could get people to open their minds, hearts and their pocketbooks. It was a big loss when he passed away. There’s only one Father Biltz, that’s for sure,” Msgr. Friend said.

The death penalty advocate who keeps fighting for the lives of inmates: “Continue to reach out to people that maybe other people think are not worthy of that,” Nixon said.

The black priest who has vowed to carry the torch to support modern day civil rights: “I think he taught me the significance of taking a stand for the rights of the marginalized. They need an advocate who would be a spokesperson for people who could not speak for themselves,” Father Harvey said.

The parish priest and nephew preaching love for the poor at the pulpit: “To not only care for the needy and the poor, but to help them have more opportunity to come out of their situation of poverty,” Father Elser said.

The deacon who knows the power of the communion of saints: “Yes, this is very inspiring to know people like him really cared for the people in need … following those steps is why I do what I do,” Luna said.

And the friend and brother priest who has carried that fiery spirit with him throughout his priesthood.

“He would be at the forefront of equal rights or privileges for women, he would be certainly against those people who demonstrate against homosexuals,” Msgr. O’Donnell said. “He was very fair, very just in terms of justice. He would believe on the Christian side, the side of Jesus, where you accept all people and you don’t condemn all people.”

Though Msgr. O’Donnell admits his friend would be “very embarrassed” to be called a prophet, it’s the legacy he left.

“Joseph left a legacy in a quiet way on one hand and a militant way on the other hand,” Msgr. O’Donnell said. Looking away, he added, “I can’t believe it’s been 30 years.”

Please read our Comments Policy before posting.

Article comments powered by Disqus Teens put their social teachings boots on the ground

Teens put their social teachings boots on the ground

Archbishop offered peace Mass ahead of Chauvin verdict

Archbishop offered peace Mass ahead of Chauvin verdict

Diocese eyes bills before Arkansas Legislature

Diocese eyes bills before Arkansas Legislature

A Catholic You Want to Know: Raymond Bertasi

A Catholic You Want to Know: Raymond Bertasi

Pro-life weekend scaled back to smaller Cathedral Mass

Pro-life weekend scaled back to smaller Cathedral Mass

Winning directory photo honors Our Lady of Guadalupe

Winning directory photo honors Our Lady of Guadalupe

St. Paul says: How does the Bible define love?

St. Paul says: How does the Bible define love?

6 steps to getting married in Diocese of Little Rock

6 steps to getting married in Diocese of Little Rock

Most frequently asked questions on Catholic marriage

Most frequently asked questions on Catholic marriage

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

St. Joseph a model of solidarity with immigrants

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Two gifts after Jesus’ death: Virgin Mary and Eucharist

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Why we have an altar, and not just a communion table

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Pope: Wars should be resolved through nonviolence

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist

Living relationship with Jesus Christ in the Eucharist